"Information smacks of safe neutrality; it is the simple, helpful heaping up of unassailable facts. In that innocent guise, it is the perfect starting point for a technocratic political agenda that wants as little exposure for its objectives as possible. After all, what can anyone can say against information?"- Theodore Roszak

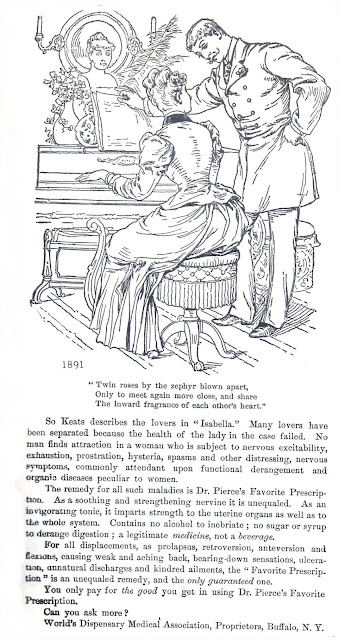

Originally published in 1891, the advertisement for “Dr. Pierce’s Favorite Prescription” – alleged to remedy such feminine “maladies” as “nervous excitability, exhaustion, prostration, hysteria,” as well as imparting “strength to the uterine organs” – shows some surprisingly complex political and cultural undertones. Although it is not specifically noted where this advertisement first appeared, we can assume that an advertisement of this sort would most likely have been published in a journal or magazine marketed exclusively for women. The undercurrents of political and cultural notions arise precisely in regards to its form as a newspaper advertisement and from its content as addressed specifically to women’s interests, which in turn mark it as indoctrinating the patriarchal ideological stances of the particular era.

As Jürgen Habermas

outlines in The Structural Transformation

of the Public Sphere, the shift from solely private activities to public

discourse amongst a widespread sphere of influence was marked by the rise not

only in public spaces such as coffee-houses but also in the proliferation of

affordable printed materials such as books and newspapers. Furthermore, up

until the eighteenth century, “advertisements occupied only about

one-twentieth” of political or cultural journal space, as most business

communication was conducted either face-to-face or by word-of-mouth (Habermas

190). However, it was around the middle of the nineteenth century that

advertising agencies became solidified business models. As newspaper and

journals increasingly relied on selling advertising space in order to turn a

profit, the publisher’s job was shifted from “a merchant of news to… a dealer

in public opinion” (Habermas 182). Indeed, we can see this manifested in the

advertisement, especially since the name of the product – “Favorite

Prescription” – marks it has having some sort of societal approval and

necessity. By keeping in mind Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin’s notion in Remediation that “no medium [seems to]

function independently and establish its own separate and purified space of

cultural meaning,” to some extent the rhetoric of the printed advertisement

seems to remediate the rhythm and persuasive techniques of the sales pitch of

the door-to-door salesman, albeit in a much more “public” setting, i.e. a

newspaper with a high circulation (55).

One major

criticism of Habermas’s notion of the public sphere is its notable exclusion of

women. Habermas seems to peg this as a result of the “nobility joining the

upper bourgeois stratum [that] still possessed social functions… [of] landed

and moneyed interest”, thus resulting in conversations that included “economic

and political disputes” (33). Evidently, according to Habermas, women would not

be interested in such intellectual pursuits, and thus were neglected in terms

of participation in the public sphere. However, he does note that it was

“female readers… [that] often took a more active part in the literary public

sphere,” constituting a reading public that held some significant economic sway

(Habermas 56). Perhaps then this is the reason that the market for women’s

journals and magazines, aimed at their interests, came about well before equality

for women in the political realm, including the right to vote, which happened

almost thirty years after “Dr. Pierce’s” was published. Furthermore, the

advertisement’s likely publication in a women’s newspaper or journal, itself a form

of media which “developed into a capitalist undertaking… [fueled by] a web of

interests extraneous to business,” particularly shows its primary goal of

selling a product, not necessarily providing women with the tools or

opportunities for rational-critical debate (Habermas 185).

It is at

the intersection of form and content that we can begin to see the underlying

function of such advertising as related to Althusserian notions of ideological

apparatuses, as well as the inherent attitude of the dominant patriarchal

society. By considering Althusser’s thesis that ideology has physical

properties, then we could argue that this particular advertisement, as

published in a newspaper or journal, shows what Habermas sees as the

“psychological manipulation of advertising” (190). As such, the language of the

advertisement is directed to women by appealing to their insecurities. Of

particular notice are the phrases “Many lovers have been separated because the

health of the lady in the case failed” and “No man finds attraction in a woman

who is subject to [the various disorders]”. What is subverted in this

particular advertising technique is the fact that the “sender of the message

hides his business intentions in the role of someone interested in the public

welfare,” in this case, of the individual lady who might be suffering from

these thoroughly Victorian aliments (Habermas 193). Furthermore, the

illustration works to continue the “psychological manipulation” by

characterizing the male gaze. Much like Dürer’s woodcut, here the “desire for

immediacy is evident in [the man’s] clinical gaze, which seems to want to

analyze and control… its female object” (Bolter 79). The man stares at the

woman seated in front of the piano, turning the page of her music notes almost

like an austere school-master. He holds the position of authority, standing

above her, and thus she is regulated to a position of adolescence, fragility

and obedience. Bolter and Grusin later make the argument that the male gaze in

linear perspective “depends on hypermediacy, which is defined as an ‘unnatural’

way of looking at the word” (84). However, Althusser would argue that the

interpellation process so engulfs society in ideological viewpoints that we are

unable to see things any differently. For the women of this time period,

lacking political and social equality, a masculine authority admonishing them

for “undesirable” traits (i.e. the “organic diseases peculiar to women”) might

be enough to persuade them to immediately go out and purchase the advertised

product. Habermas extrapolates this claim by noting that “ideology accommodates

itself to the form of the so-called consumer culture and fulfills… its old

function, exerting pressure toward conformity” (215). It is precisely that

conformity to the patriarchal notions of the differences between the sexes that

is played out through this particular advertisement.

(Word count: 972)

---

Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and Ideological State

Apparatuses.” Literary Theory: an

Anthology 2nd Edition. Eds. Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan. Malden: Blackwell

Publishing, 2004. 691 702.

Print.

Bolter, Jay David and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2000. Print.

Clymer, Floyd. Scrapbook:

Early Advertising Art. New York:

Bonanza Books, 1955. Print.

Habermas, Jürgen. The

Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: an Inquiry Into a Category of

Bourgeois Society. Cambridge:

The MIT Press, 1991. Print.

Webster, Frank. Theories

of the Information Society 3rd

Edition. New York:

Routledge, 2006. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment